Why Superhero Themes Are Behavior Change Kryptonite

With a massive teacher shortage looming in the Orlando area, the local school district recently put up an ad on a giant billboard just outside the main campus of the University of Central Florida. “Become a Hero,” the billboard reads. “Teachers Needed.”

There’s only one problem: in our research, calling people heroes makes them feel just the opposite.

Firefighters? No way. Parents? Not even close. Kids? Maybe, but only when they are pretending. Teachers? They are just trying to survive.

So it’s interesting that hero and superhero themes are so popular among advertisers, especially in behavior change marketing and public interest communications arenas. Understandably, it’s visually appealing – who doesn’t like a cute kid in a cape? And aren’t people who are doing the right thing truly society’s heroes?

The problem is calling someone a hero too often makes them feel like an imposter. As a result, it’s a turnoff. Even people with the courage to run into burning buildings or to daily take charge of 25 unruly five-year-olds are deeply aware of all the ways they are just plain, ordinary, flawed human beings. And when you call them a hero you can inadvertently make them feel inadequate to the task as well as deeply misunderstood.

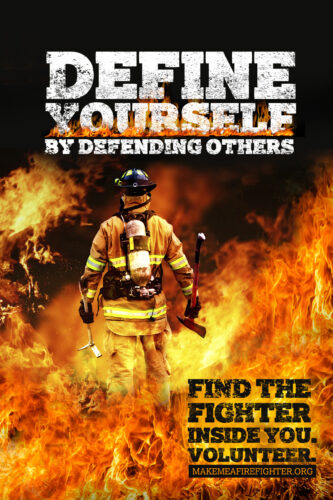

Last year, we helped the National Volunteer Fire Council launch a campaign to reverse a downward trend in recruitment. Our research found firefighters emphatically did not see themselves as heroes. But we uncovered three behavioral levers we could pull to help turn potential recruits into new volunteers: 1) self-standards: they saw themselves as capable and handy, the kind of guy or gal who can run big equipment and fix things with their hands, 2) belonging: they identified with being part of a tight-knit crew, and 3) efficacy: they needed an offer of training to help them feel like they were up for the job.

As a result, our Make Me A Firefighter campaign, rolled out in volunteer fire stations across the country, skipped the hero theme entirely.

Our anti-hero hypothesis was further confirmed in recent focus groups with mothers of infants. We had a test ad that asked, “Why is supermom super tired?” Interestingly, the ads played well in a Southeastern city and bombed in the Midwest.

Turns out, what divided the two groups was neither geography nor liberal v. conservative culture, but the fact that the Southeastern group happened to be mostly stay-at-home moms and the Midwesterners were women who worked. While both groups were very tired, the working women were heartbreakingly exhausted and torn by feeling like they weren’t measuring up either on the job or at home.

Women in both groups said they “felt like a good mother” when they managed to fulfill their family members’ needs and still get their to-do lists done — something the working women were rarely able to pull off. So while the working moms’ efforts to juggle so many balls on just a few hours of sleep a night might be defined as heroic, they usually felt just the opposite. And as a result, they hated the Supermom ad.

Personally, I’ll never forget the time when my kids were little and a stranger leaned over to me in the cafeteria at my local science center and pronounced “You are a good mother.” At the moment, I was single-handedly managing five children under age seven (three of them mine, plus a niece and nephew), and by some miracle had managed to get everyone happily settled despite the usual sibling rivalry and a banged shin. This guy went on to say, “I’m a teacher. If there were more mothers like you, my job would be easier.”

In a way, he was calling me a hero. And although I politely thanked him, my true reaction entailed words not printable in this blog. It’s still hard for me to articulate why this interaction so ticked me off, but it included thoughts of “you don’t know me” and “who are you to judge,” as well as an instant internal replay of my many not-so-stellar mother moments (some of which still haunt me today).

That’s why next time you feel the urge to deploy a superhero theme, try asking your target audience first how that makes them feel. Chances are, you may learn it just won’t fly.

Sara Isaac is the agency’s chief strategist.