Want Green Behaviors? Stop Focusing on the Environment.

The problem with going green is all the gray.

Humans like black-and-white thinking. Good or bad. Friend or foe. Truths or lies. Our deep seated ambiguity bias — summed up in the saying the devil you know is better than the one you don’t — can make us stick to a product or behavior or process or system we know well rather than switch to a potentially better option we are not sure about.

And by and large green choices are nothing if not ambiguous.

Will that green cleaning product work — and how bad could the usual stuff be if it’s sold on store shelves? Is that reusable grocery bag better for the environment if it ends up in the landfill? Does cooking at home reduce my carbon footprint if I end up throwing out a lot of food? And should I buy a hybrid car given those battery issues I’ve vaguely heard about?

To make things worse, it’s no longer enough for a product to be green, it needs to be net-green — a calculation of total life-cycle impact from product birth to death. Yes, this is important. It also makes consumers’ green decisions that much more complex.

We are full of green intentions

When I ask my clients not to lead with green in their sustainability initiatives, they often are dumbfounded. How could I even suggest that? People support environmental action! They want to do more!

If you look at what people say, my clients are right. A multitude of opinion polls have shown broad support for the environment. A large majority of Americans want the government to do more to protect the environment and fight climate change.

We also say we’re walking the talk at home. A 2019 Pew Research Center study found that nearly 9 in 10 of us say we act sustainably some or all of the time. More than two-thirds of the respondents reported using fewer single-use plastics and reducing food waste to help the earth.

But our trash tells another story. Digging into the dump shows we are using as much single-use plastic as ever and throwing even more food away.

The ‘say-do’ gap: where green turns brown

Green products and behaviors are frequent victims of what many behavioral scientists call the say-do gap. Many of us like the idea of being green, and self-positivity bias leads us to think we are doing more for the environment than we actually are.

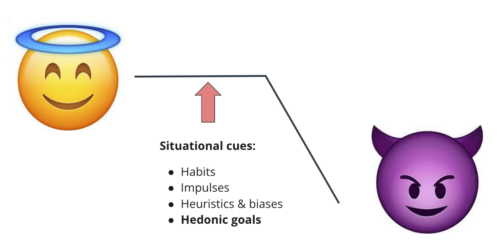

But while we may walk into a store or start our day fully committed to acting green, our green intentions can get hijacked by things like habits, norms, cognitive overload, and hedonic impulses (yielding to temptation).

Or maybe it’s just that your inlaws are coming this weekend and the bathroom has to be spotless. And you’re not sure that green product is up to the task.

There are three main reasons why, in the moment of truth, it’s often hard for us to lean green.

- We think green products are more expensive. There’s a reason why the nickname for Whole Foods is Whole Paycheck.

- We think green products are inferior. In the past, they often were.

- We don’t like to be preached to. And environmentalists can be a preachy lot.

The problem with greensplaining

When McDonald’s and Coke sell fries and a soda, they don’t talk about the larger contexts of obesity or diabetes, or detail the intricacies of their manufacturing. They sell happy meals and promise to “add life” to your life.

But when it comes to pitching green products or sustainability initiatives, marketers can fall into what I call “greensplaining.” They focus on telling people everything there is to know about how the product or behavior will help the environment.

They forget to focus on how it will solve a problem or pain point for the consumers themselves.

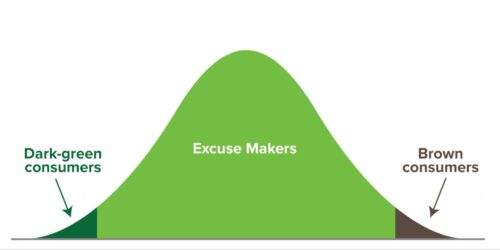

The result? After years of studying all the ways that people say they support the environment but fail to make green choices, UCLA behavioral scientist Magali (Maggie) Delmas created a bell curve of green behavior that shows what we actually do instead of what we think we do.

We are a nation of green excuse makers.

So what’s a green marketer to do?

A key finding from Maggie Delmas’ research is that consumers are LESS LIKELY to buy a product if they think its green benefit is the primary driver. And they are MORE LIKELY to buy a product if the green benefit is seen as a fortuitous side effect.

In other words, if a product happens to be green, that’s great. But if green is its main goal, consumers think it is probably inferior. In most instances, sustainable co-benefits generally should be a plus — not the main reason for the product.

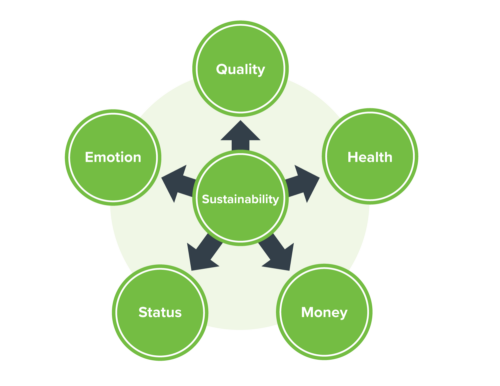

Maggie Delmas recommends using a “Green Bundle” that pairs your product with other features that consumers are shopping for, including quality, health, money, status and emotion.

How to use the green bundle for behaviors

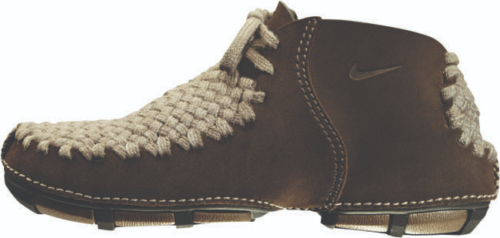

Green products have come a long way since Nike’s 2005 launch of “Considered,” the earthy brown sustainable shoes that customers hated, critics called the Air Hobbit, and Nike quickly took off the market. Marketers are getting better at making sure their sustainable products fit with what consumers otherwise expect from their brand.

But behavior change campaigns are where greensplaining runs especially rampant. Conservation or sustainability initiatives often start with a nonprofit or government agency thinking of all the things they want to tell people about why a behavior is important, rather than thinking through how to make the behavior align with the audience’s needs and values.

At M4C, one way we avoid the Say-Do Gap is by analyzing our audiences’ pain points and need-states and then using our Behavioral Determinants Framework to align behavioral cues with the desired behavior.

A good example is how we revamped a water conservation campaign for the City of Santa Monica, Calif. The state was in severe drought and the City had mandated every household, business and city agency cut their water use by 20%. But in a City filled with beachside millionaires, even a substantial fine could easily be absorbed as the price to pay for luxury.

At the time, the city had been running an “Every Drop Counts” campaign. They had also pushed out messages about how saving water saves money, a favorite tactic of most water conservation campaigns. Question: when’s the last time you parsed your water bill to see how you could save $10 — before heading to Starbucks to drop $4 on a latte?

There are three key facts about Santa Monicans: they are very green, very wealthy, and very trendy in a beachy sort of way. Residents support environmental protections — but they also have houses with 14 bathrooms (I’m not kidding) and a lifestyle image to protect. Suggesting taking shorter showers to save a few bucks wasn’t going to cut it.

So instead of telling Santa Monicans to save money, we asked them to spend it instead. We leveraged their social identity as tech-forward green revolutionaries, and promoted investing in high-efficiency home and yard appliances that could save water for them.

We gave Santa Monicans what they wanted — a way to live their values without sacrificing their lifestyle. And our advertising poked a little fun at the sacrifice ethic. Why do the hard thing when the easy thing is more effective?

The city not only achieved — but surpassed — its water conservation goals.

Sara Isaac is the agency’s chief strategist.