Sex, Death and Social Marketing: 2 Design Sprints

How do you get older adults to use condoms? How do you empower terminally ill people to take control of their healthcare?

A design sprint can help.

At the World Social Marketing Conference in Washington, D.C., this week, two different workshops showcased how hands-on, time-limited campaign design approaches can help behavior-change marketers tackle tough social issues.

In the first workshop, master’s student Natalie Bowring and Professor Rebekah Russell-Bennett from the Queensland University of Technology put participants to work thinking through how to promote condom use to reduce sexually transmitted diseases among older adults.

In the second, Meisha Thigpen and Peter Mitchell from our Marketing for Change team led a sprint to brainstorm ideas for how to get doctors on board with two new patient empowerment tools that we developed for Compassion & Choices.

So what do sex and death have in common? Well, centuries of poetry has been devoted to both subjects. They are topics that most people avoid talking about in polite society. But they also — like pretty much any issue at all — can be successfully tackled with a well-structured design sprint.

Although sprints can take different forms, they usually share these four steps.

Step 1: Create ‘personas’ to represent your target audiences. Both sprints asked participants to start by creating personas. These fictional user profiles, borrowed from the tech world, include a name, picture, age, gender, family background, “needs states” and “pain points.” Creating a concrete, composite character to represent your audience and what they want and need – and where your campaign can address those wants and needs – helps keep all proposed ideas squarely centered on the user.

In persona exercises, I always enjoy how quickly people can imagine a member of the target audience and bring them to life. In the STD prevention sprint, I worked together with a woman from Johns Hopkins University. In just a few minutes we created a profile for a man we named Wally Widower, who we decided was lonely, somewhat depressed, and had one adult son who lived far from home. He was desperate for intimacy but still missed his wife, felt awkward about socializing, and didn’t want to be presumptuous by planning ahead and buying condoms before a date.

Across from us, another group created a player persona, a man who liked to pursue sexual conquests. This guy didn’t like to wear condoms because he thought they reduced sensation, and he also liked the thrill of risk. My workshop partner and I both agreed he was a douche, but a believable one. It was funny how much we disliked the guy — and how clear it was we would need a segmented approach to market condom use to both him and Wally.

Step 2: Get ideas — fast. The goal of a sprint is not to carefully craft the perfect idea. It’s to quickly brainstorm as many ideas as you can. As Meisha noted in the workshop, a half-baked idea can later develop into something really good. You just have to get it down on paper to get the process started.

This is where establishing time limits can help. It helps people overcome the fear of having “bad” ideas and overthinking their responses. In our Marketing for Change sprint, we distributed sticky notes and conducted a “Quiet Storm.” We set the timer for 5 minutes and asked people to come up with at least 10 ideas, one idea per note. Participants quickly covered the backs of the folding chairs in front of them with hastily scribbled Post It Notes. (One advantage of this exercise is it puts introverts on equal footing with their extroverted counterparts. One disadvantage is sometimes the ideas come so fast and furious that participants have trouble reading their own handwriting).

Step 3: Collaborative design. Probably the most important element of the sprint process is that it compels people to work together. Collaboration is energizing. It helps people search for the kernel of good in a bad idea, or it encourages them to let solid ideas flourish.

In the patient empowerment sprint, after the Quiet Storm, we gathered people into small groups where they discussed their ideas, chose the top three, and presented their best ideas to the workshop as a whole. It always surprises me how often people think up confluent ideas, and how those ideas gain depth and breadth through discussion.

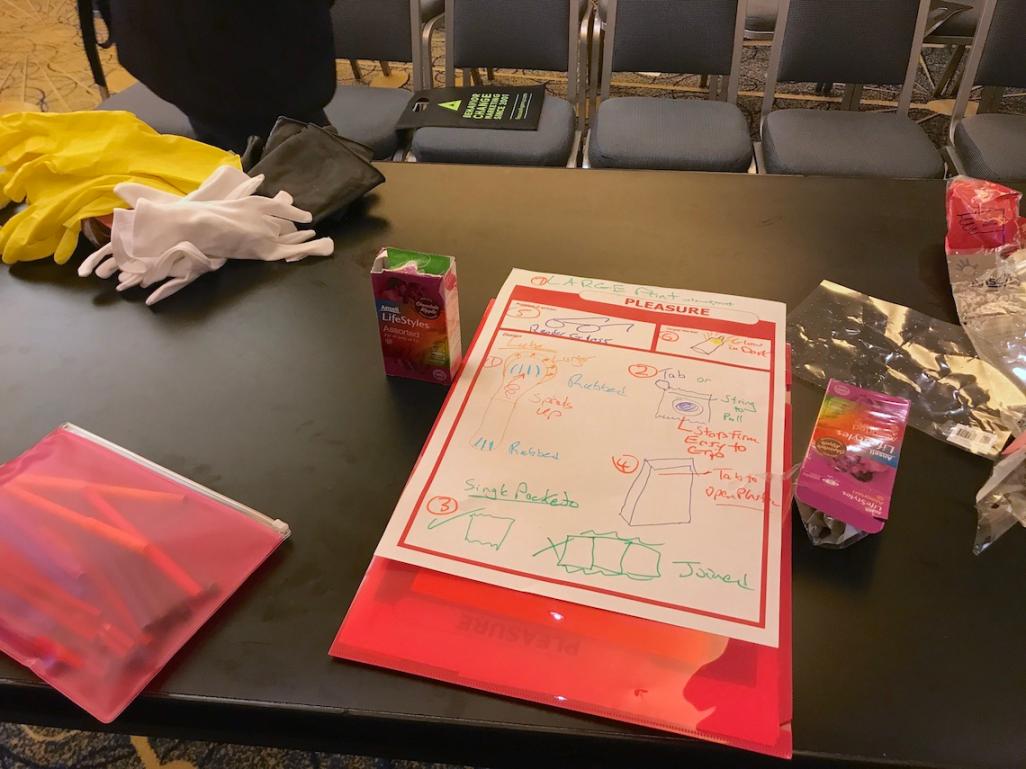

In the STD prevention workshop, we also worked collaboratively throughout. The group with the most fun assignment gathered around a table containing several boxes of condoms, a tube of lubricant, and rubber gloves. The gloves were used to simulate the loss of dexterity that can come with aging and the onset of arthritis.

As glove-wearing participants attempted to unwrap condoms and open the lubricant, they began to brainstorm lots of clever ways to make the products more useful and more appealing to their reluctant older adult target audience, including creating condoms with a glow-in-the-dark tip to help people with aging eyes put on a condom in mood lighting.

Step 4: User testing. Of course, our workshops weren’t set up for end-user research. But in real life, a design sprint is not complete until the product or ideas created have been tested with users, and revised as needed. For Compassion & Choices, our five-day design sprint to develop the Diagnosis Decoder and Trust Card included a full day of user testing on the last day.

For me, the biggest takeaways from the design sprint sessions were how the right process can foster creativity. Innovation and inventiveness may just spring fully formed from the brain of a few super-talented people. But it also can spring from the collective brain of a fired up group of people with clear direction and a deadline. You likely already have the right people around you to create new and creative approaches to the social issues you care about. They just need a clear direction and a clear deadline. And permission to have a little fun.

Sara Isaac is the agency’s chief strategist.