If We Want A Healthier Nation, We Need to Talk About Race and Privilege

If you’ve worked in philanthropic spaces long enough, you’ve been there: in a posh hotel that 80 percent of Americans could never afford, surrounded by well-heeled white people and some brilliant people of color with Ivy League degrees, where the topic at hand is health equity and social justice. To be fair, it’s essential that these conversations take place in the halls of privilege that have the power and resources to make a systemic impact. But it also makes for a startling change of pace when you find yourself at a different kind of philanthropic forum — like a few I have attended recently in Florida at the Foundation for a Healthy St. Petersburg, where your small group discussions are just as likely to include a formerly homeless preacher or a black leader of a local nonprofit as they are to include yet another well-educated, well-meaning white person (like me).

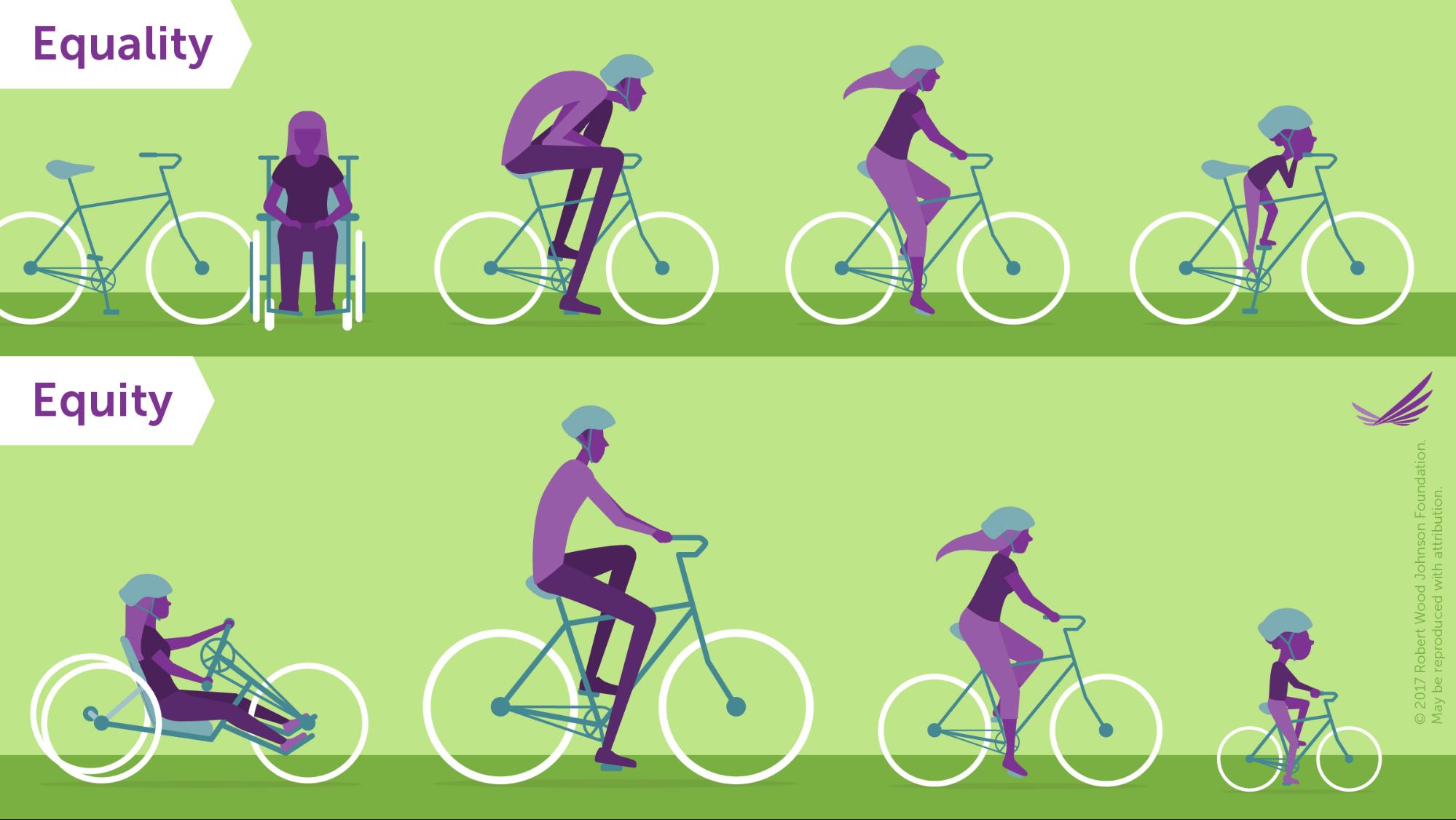

Why is health equity important? Despite spending twice as much on healthcare per person than other wealthy countries, Americans live shorter and sicker lives — and whether you are healthy or sick depends to a large extent on your family income, ethnicity, and zip code. So while many health interventions over the last decade have been focused on helping people make mostly individual lifestyle choices that can vastly improve health, these types of efforts don’t address many of the root causes.

Tackling the social determinants of health is really tough, though, and not just because progress will require systemic changes across housing, transportation, education and more. Also standing in the way: America’s dearly held myth of meritocracy, and our inability as a society to talk about racism and privilege in an honest and constructive way.

The myth of meritocracy

Last month, the UN Human Rights Commission delivered a scathingly plain-spoken report on extreme poverty in America. The report addressed one of the main pillars that prop up continued health disparities — a myth that can be traced back to our Puritan forebears who believed wealth was evidence of godliness, and poverty a sign of heavenly disfavor. The UN’s special rapporteur wrote:

In thinking about poverty, it is striking how much weight is given to caricatured narratives about the purported innate differences between rich and poor that are consistently peddled by some politicians and media. The rich are industrious, entrepreneurial, patriotic and the drivers of economic success. The poor are wasters, losers and scammers. As a result, money spent on welfare is money down the drain. If the poor really want to make it in the United States, they can easily do so: they really can achieve the American dream if only they work hard enough. The reality, however, is very different…

Why do black babies die at twice the rate of white babies? Why do Puerto Ricans suffer higher rates of asthma? Why do people without college degrees suffer more chronic diseases? Poverty is part of it. And blaming people for being poor — and turning a blind eye to the social and political structures that favor one race and gender over others — is part of it, too.

How to talk about race and privilege

Robert Wood Johnson Foundation argued in a comprehensive report on health equality last year that, in addition to poverty, structural racism and discrimination — and how these impact the distribution of power and resources — matter more than health care in shaping America’s health disparities.

Robert Wood Johnson Foundation argued in a comprehensive report on health equality last year that, in addition to poverty, structural racism and discrimination — and how these impact the distribution of power and resources — matter more than health care in shaping America’s health disparities.

But how do you talk about structural racism and discrimination constructively? A couple of years ago, I was dragged by friends to a workshop by Peggy McIntosh, a professor, feminist and racism activist who literally wrote the book on white and male privilege in the late 1980s. I grew up with a single mom and a healthy dose of family dysfunction, and never considered myself “advantaged.” I’m also originally from California, not Orlando where I now live, and I don’t feel personal or familial responsibility for the racial terror and segregation that were facts of life in this community until just a few generations ago. But after Peggy’s workshop, I walked away with an understanding of how the color of my skin surrounds me with invisible social protections that I hadn’t ever noticed because they had always been there.

Peggy’s SEED curriculum (Seeking Educational Equity and Diversity) uses serial testimony, an unusual approach to conversation that creates space for every person to tell their personal truth. It is awkward, and powerful. In Orlando, the Valencia College Peace and Justice Institute also uses this method. I ended up by chance recently in a serial testimony led by the Institute at the city’s annual conference for neighborhood associations. I sat knee to knee with an elderly black woman — she in a nice dress and hat, me in a T-shirt and jeans. We both lived in downtown Orlando, me in a historically white neighborhood and she in a historically black neighborhood on the other side of aptly named Division Street. In her testimony, she ended up telling me simply and without malice: “I just can’t trust white people.” Since serial testimony does not allow replies — and thus eliminates pontificating, advice-giving and excuse-making — I sat with that, as a white person who likes to think of herself as “good.” And I still sit with that today.

The Foundation for a Healthy St. Petersburg has made health equity its primary focus, and it has undertaken a number of initiatives to tackle that. It is using data, such as it’s just-published Health Equity brief, to identify the community’s most pressing health disparities. It is opening a Social Change Center, which will be designed to engage all sectors of the community — business, government, faith and nonprofit — in activities and programs to advance health equity. And it is helping the community learn how to talk about race and privilege.

For several years now, the Foundation has held two-day Courageous Conversations workshops in St. Petersburg multiple times a year. Although Courageous Conversations was originally intended to help uncover and address personal and institutional racial biases in schools, Foundation CEO Randall Russell says teaching his community to have cross-racial dialogue is key to tackling health equity.

As Courageous Conversations founder Glenn Singleton said at a kickoff meeting for a workshop last fall, “you can’t change that which you can’t talk about.”

Let’s start a conversation.

Sara Isaac is the agency’s chief strategist.