Hurricane Irma’s Water Crisis: How Scarcity Messaging Can Backfire

I first noticed that hurricane hysteria was setting in on Labor Day. My husband and I stopped at a Central Florida supermarket on the way home from the beach, and it was a mad house. Lines were long and tempers were short. And it seemed nearly every person in there had a cart –– sometimes two –– full of bottled water.

“Should we be getting water?” I asked. My husband gave me the death stare of a South Dakotan who has lived through blizzards and the country’s second most deadly flash flood and knows when there’s an emergency, and when there is not. We grabbed a sandwich and went to a local brew pub instead.

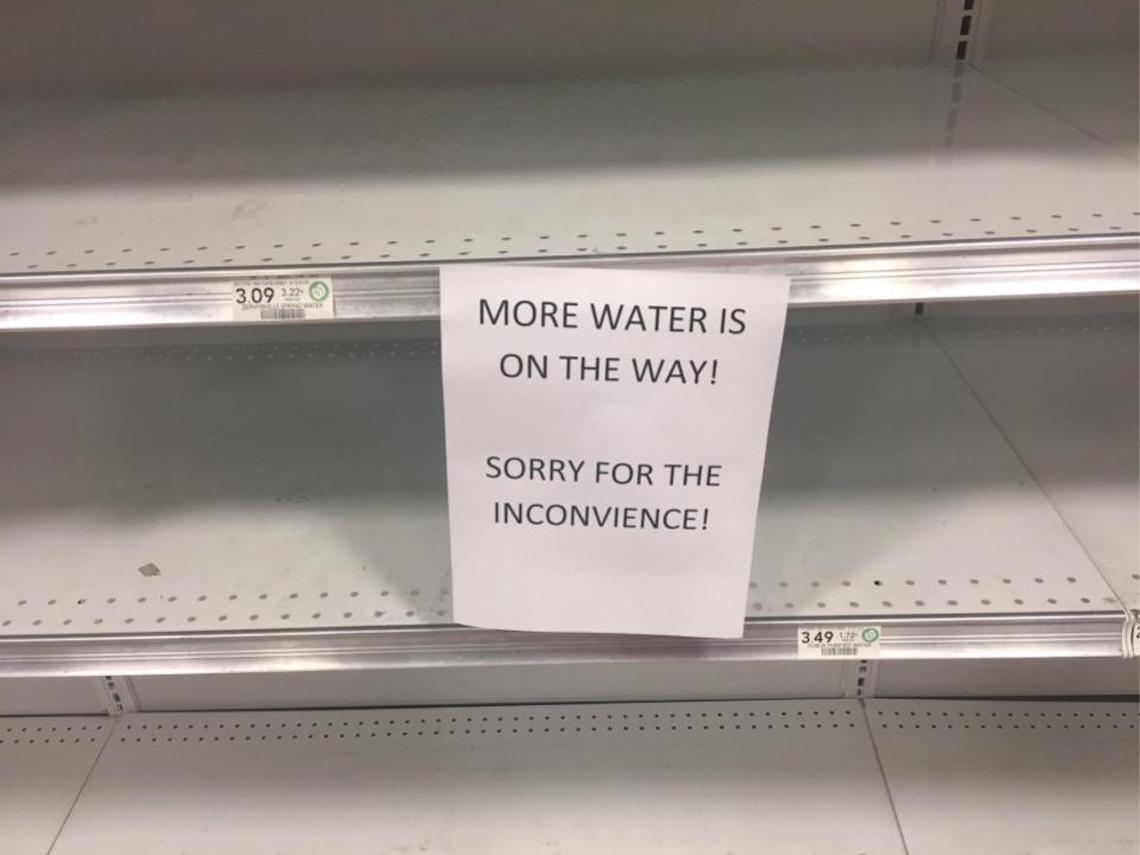

By Tuesday –– five days before Hurricane Irma hit Florida –– stores throughout the state were running out of water. In my neighborhood in downtown Orlando, people began posting bottled water queries and sightings on Nextdoor.com. By Thursday, desperation set in, leading Orlando Sentinel columnist Scott Maxwell to joke on Facebook that Irma must have somehow wiped out the community’s tap water before making landfall.

I ducked into a grocery store twice in the runup to the storm. Both times, I missed the crowds (people were lining up two hours ahead of the store’s 7 a.m. opening), which meant I also missed the clear must-have items. Bread: gone. Water (of course): gone. Toilet paper: gone. Meanwhile, I happily stocked up on the plentiful long-life produce –– apples, pears, carrots and celery. (Although I have to admit that, infected by the generalized panic, I grabbed a jumbo box of Goldfish crackers that is still sitting unopened in my pantry).

I’m not opposed to bottled water. Although tap water is my default choice, bottled water is a great alternative to soda when tap water is not available. As Irma barrelled toward Florida, I probably would have bought a case of water if my neighbors hadn’t scooped up carts full.

But I wasn’t worried. I had lived through Orlando’s 2004 trifecta of hurricanes (Charley, Frances and Jeanne) and guessed from experience that my neighborhood would lose power but not water. I also knew we weren’t likely to have mass flooding like Houston, but if we did we would end up fleeing and would have to leave all that bottled water behind anyway. So I filled up every reusable water bottle and pitcher in the house, and used Tupperware and Ziploc bags to make homemade blocks of ice.

As a behavior change marketer, I was fascinated by how scarcity mentality affected behavior, and how even against my better judgment I could feel its contagion. But I think Irma also holds important lessons for environmental and public health agencies and advocates who want people to behave in new and different ways.

The default messaging approach for many groups is to try to create a sense of urgency by leveraging scarcity and crisis. Our water supply is drying up. Overconsumption is killing off wildlife. Climate change is threatening the world’s food supply.

Looking at Hurricane Irma, it’s clear that the problem with this approach is that crisis and scarcity activate irrational System 1 thinking, sending people into hunker down and hoarding mode. It can, in fact, motivate people to consume more rather than less of the resource that is perceived to be scarce. It activates our get-and-protect-what’s-mine instincts rather than our more rational (and generous) selves, and encourages us to focus on what is immediate rather than what is important.

Meanwhile, as I predicted, my house never lost water. We got power back on after just 48 hours. We emptied our containers and put them back in the cupboard.

That’s not to say Irma hasn’t been a disaster in the true sense of the word. In Central Florida, at least eight people have died, mostly from traffic accidents during the storm or from carbon-monoxide poisoning caused by bringing generators inside a house or attached garage. Nearly 430,000 people still do not have power. Debris lines every street. Traffic lights still are not working, and the biggest problem, aside from some spot flooding, is sewage overflows from lift stations that lost power.

We have weeks of cleanup ahead, with temperatures expected in the upper 80s and 90s. As we rake and wash and reorder in the sweltering heat, there will be lots of opportunities to drink up all that stockpiled water. Or better yet –– now that the fears of scarcity have passed –– offer it to the linemen and sanitation workers who are hard at work putting our community back together.

Sara Isaac is Chief Strategist at Marketing for Change.