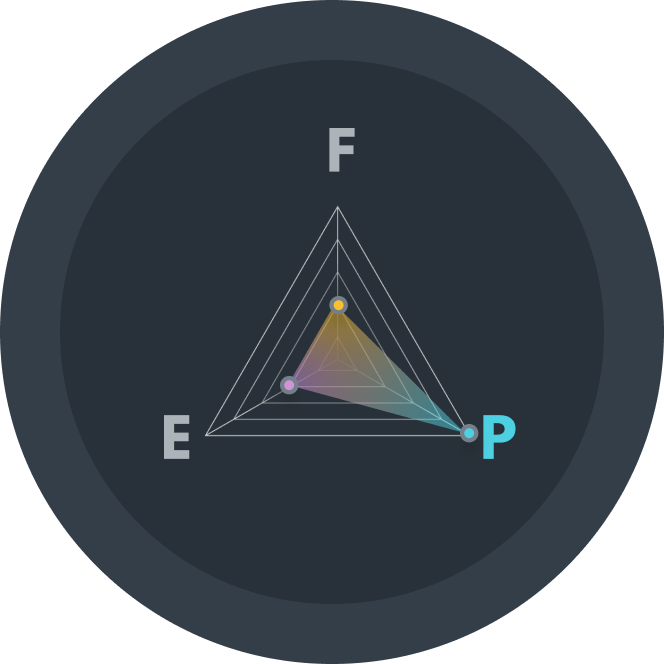

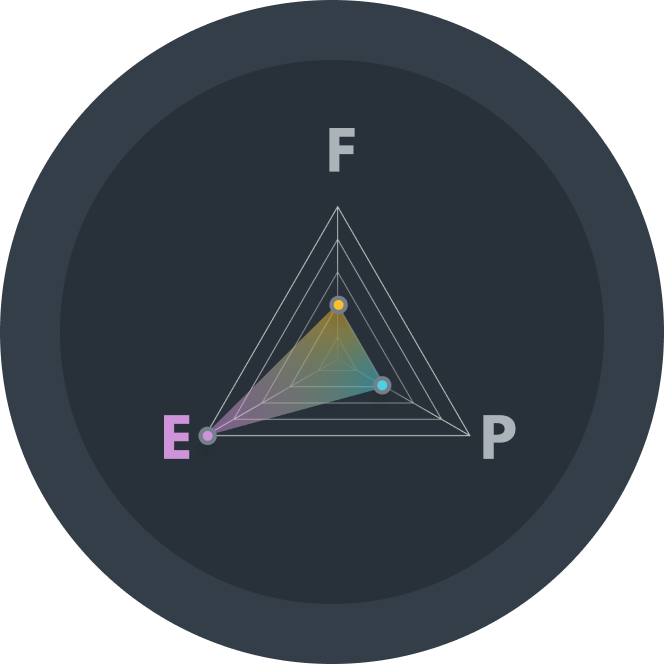

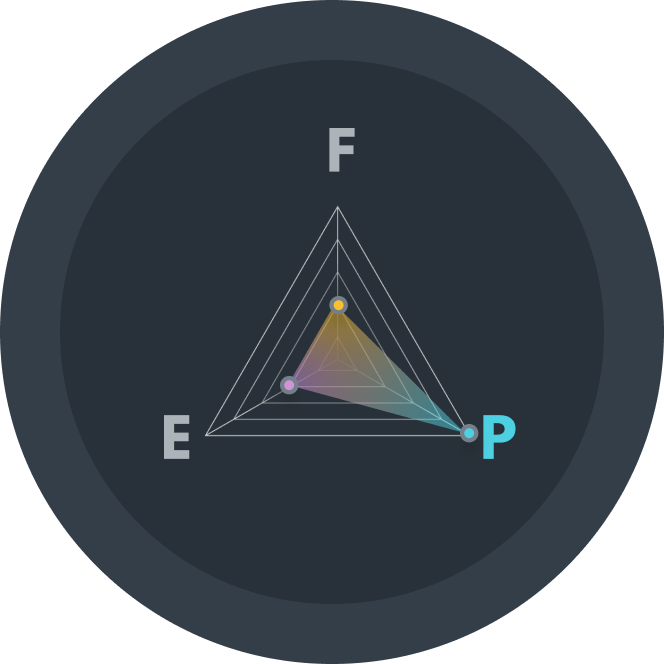

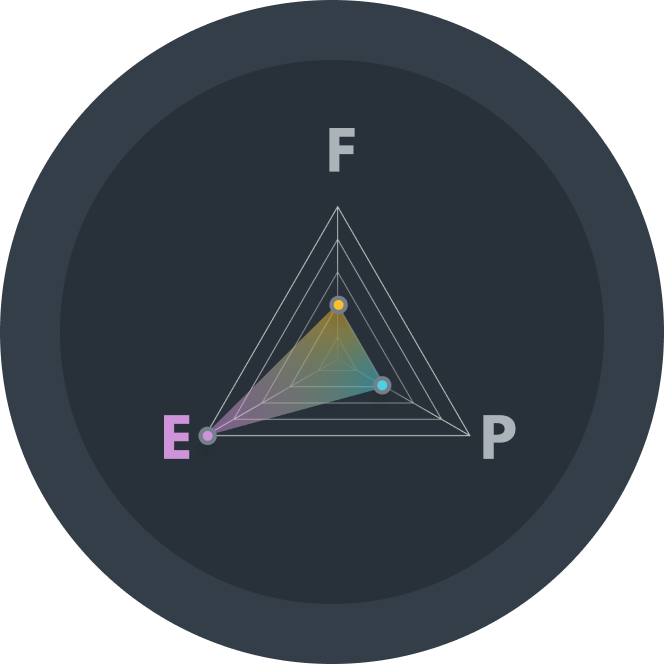

The Behavioral Determinants Framework

To simplify it all, we categorize these behavioral determinants into three categories: Fun, Easy and Popular. After all, fun, easy and popular is the heart of why we humans do just about anything. The Behavioral Determinants Framework helps us frame target behaviors to address an audience’s own wants and needs rather than trying to convince them to change their values and beliefs. Explore the determinants below.

What people expect to happen –– good or bad –– are the things we call perceived consequences. “We’ll start with the good consequences. (We’re in the Fun category after all.) What we’re talking about here is rewards or benefits people expect to get after doing a certain behavior. When using good perceived consequences, the sooner and surer the reward seems to be, the more powerful it is.

Now for the bad perceived consequences. Losing something looms larger than gaining something (a concept known as loss aversion), but the outcome has to be certain. In fact, people will undervalue likely outcomes relative to certain outcomes (certainty effect).

The key word to remember here is perceived — it’s what people expect to happen that matters.

High risks may deter us. But the influence of risk is hampered by optimism bias and the complexity of grasping probability. It is also a very crowded messaging category: In a blizzard of warnings, each individual caution is easily lost or dismissed. Risk is most powerful when the threat is highly probable, imminent, personal and easily addressed. Otherwise, other determinants are much more likely to play a larger role in influencing behavior.

How you feel can overpower what you know. We often take action based on how we feel or in anticipation of how we might feel if we act. We seek various shades of joy and acceptance, and are triggered by feelings like anger, fear, anticipation and surprise. Just associating a product or behavior with an emotion can have a powerful effect as emotions can act as both motivators and triggers.

The chart below dates back more than 30 years. It shows how emotion is part of the evolutionary machinery for how we react to different stimuli.

| Stimulus Event | Feeling | Behavior | Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Threat | Fear, terror | Running away | Protection |

| Obstacle | Anger, rage | Biting or hitting | Destruction |

| Gain of valued object | Joy, ecstasy | Retain or repeat | Gain resources |

| Loss of valued person | Sadness, grief | Cry for help | Reattach to lost object |

| Member of one's group | Acceptance, trust | Grooming, sharing | Affiliation |

Source: Adapted from Robert Plutchik, Chapter 1 - A GENERAL PSYCHOEVOLUTIONARY THEORY OF EMOTION, Robert Plutchik and Henry Kellerman, editors, Theories of Emotion, Theories of Emotion. Academic Press 1980, Pages 3-33. ISBN 9780125587013. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-558701-3.50007-7.

Some actions require know-how or skill. Sometimes mere knowledge can trigger the intent to act, but only when the information is new and adds the necessary understanding, efficacy or inspiration people need to act.

Confidence in one’s ability to do something, which may or may not be strongly rooted in actual skill, is often a precursor to action — a missing link, especially for more challenging behaviors or more timid actors.

Behaviors are often chosen intuitively, without reflection, using instinct and mental shortcuts to lighten the cognitive load. We call those shortcuts “heuristics.” The results are predictable biases that can be used to influence behavior.

Anchoring

What people see first sets an unconscious standard by which everything that follows will be judged. Carefully designing anchors can frame a choice or target action.

Availability Heuristic

The information most readily available to us comes to mind first, even if it provides a distorted picture of reality and has a disproportionate influence on our behavior. To paraphrase Daniel Kahneman, all we see seems to be all there is.

Representativeness Heuristic

We all make judgements based on stereotypes. We overestimate the similarity between prototypes we carry in our head and a specific example at hand, ignoring realities such as the likelihood of alternative possibilities or explanations.

Optimism Bias

We tend to downplay the potential of unforeseen problems delaying, damaging or derailing an expected positive outcome. We have a bias for the best case scenario, underweighting evidence of the barriers and delays others experienced in similar situations.

Loss Aversion

We tend to favor preserving what we have over getting what we don’t. Losing $10 feels more significant than winning $10. This can play out as scarcity: When a resource appears in short supply, people think short-term, and even act against their interest to preserve what they have.

Framing Effect

Our interpretation of an event is influenced by how it is presented. Certain attributes or dangers can be emphasized or diminished depending on how the overall event is conveyed, influencing our perceptions of risk and reward, and ultimately altering what we do.

Status Quo Bias

We all have a bias toward the present situation or default, mostly because it’s easier and often feels less risky. All things being equal, we go with the way things are or what appears to be the norm. Change has a higher bar: It must be worth the effort.

Priming

You can influence the choices people make by exposing them to certain stimuli beforehand. Even getting students to focus on a random number has been shown to influence their estimates of unrelated values.

Confirmation Bias

We gravitate toward and emphasize evidence that confirms our current beliefs. We strive to maintain coherence and consistency, and contradictory evidence makes that effort more difficult -- so it can be easier to ignore it or discount its validity.

Empathy Gap

We often make rash decisions to satisfy a visceral emotion, never imagining we may soon be in another state -- what’s sometimes called moving from a “hot” to “cold” state. When you're furious, it can be hard to imagine being calm.

People like to be in control. Feeling control over a decision empowers action by providing confidence that we can make an impact. Choice helps: It gives one the sense of more control.

The perceived cost of an action — in money, time, social capital or even cognitive load — may lead to action or inaction depending on the situation. To achieve a sense of accomplishment, we often tend to finish things we’ve already invested time and energy in; on the other hand, people gravitate to what requires less of them.

Behaviors are influenced by their context. People favor what’s accessible, noticeable, supported or triggered by environmental cues.

As social beings, we can’t help but look to our peers. We are influenced by what we think others do, and by what we think they expect of us – in a word, norms. Norms can be embedded in cultures as traditions or emerge quickly as trends. While often not explicitly acknowledged or even consciously recognized by the people involved, norms are among the most powerful influences marketing can harness.

Norms come in five flavors:

Explicit Norms

When expected attitudes and behaviors are openly expressed or written down, as with laws and rules.

Implicit Norms

When we suspect what’s normal or expected even though it’s not written down.

Descriptive Norms

What we see people like us doing.

Injunctive Norms

What wins approval or disapproval from our group.

Subjective Norms

What we think others expect of us.

The standards we set for ourselves, driven by aspirations, fears and self-image, impact our behavior as we signal who we aspire to be.

Ought Self

What I should be

Ideal Self

What I want to be

Forbidden Self

What I am not allowed to be

Undesired Self

What I want to avoid being

We are always creating our “self” and signaling to others what that self is like. How we do this is driven by our vision of the kind of person we want to be and the kind of person we want to avoid becoming.

Adapted from Bak, W. Self-Standards and Self-Discrepancies. A Structural Model of Self-Knowledge. Curr Psychol 33, 155–173 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-013-9203-4

Our identity and affinity with social groups influences our perceptions and behaviors. We cherry pick data to protect our identity and our perceived value to others. Our need to fit in with affinity groups colors our perceptions of scientific evidence, regardless of our level of literacy with the topic. To motivate change, marketers must initially fit their outreach and asks to the target’s existing world view. Connection always precedes conversion.

1Kahan, Dan M. and Peters, Ellen and Dawson, Erica and Slovic, Paul, Motivated Numeracy and Enlightened Self-Government (September 3, 2013). Behavioural Public Policy, 1, 54-86, Yale Law School, Public Law Working Paper No. 307, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2319992 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2319992

What people expect to happen –– good or bad –– are the things we call perceived consequences. “We’ll start with the good consequences. (We’re in the Fun category after all.) What we’re talking about here is rewards or benefits people expect to get after doing a certain behavior. When using good perceived consequences, the sooner and surer the reward seems to be, the more powerful it is.

Now for the bad perceived consequences. Losing something looms larger than gaining something (a concept known as loss aversion), but the outcome has to be certain. In fact, people will undervalue likely outcomes relative to certain outcomes (certainty effect).

The key word to remember here is perceived — it’s what people expect to happen that matters.

High risks may deter us. But the influence of risk is hampered by optimism bias and the complexity of grasping probability. It is also a very crowded messaging category: In a blizzard of warnings, each individual caution is easily lost or dismissed. Risk is most powerful when the threat is highly probable, imminent, personal and easily addressed. Otherwise, other determinants are much more likely to play a larger role in influencing behavior.

How you feel can overpower what you know. We often take action based on how we feel or in anticipation of how we might feel if we act. We seek various shades of joy and acceptance, and are triggered by feelings like anger, fear, anticipation and surprise. Just associating a product or behavior with an emotion can have a powerful effect as emotions can act as both motivators and triggers.

Some actions require know-how or skill. Sometimes mere knowledge can trigger the intent to act, but only when the information is new and adds the necessary understanding, efficacy or inspiration people need to act.

Confidence in one’s ability to do something, which may or may not be strongly rooted in actual skill, is often a precursor to action — a missing link, especially for more challenging behaviors or more timid actors.

Behaviors are often chosen intuitively, without reflection, using instinct and mental shortcuts to lighten the cognitive load. We call those shortcuts “heuristics.” The results are predictable biases that can be used to influence behavior.

Anchoring

What people see first sets an unconscious standard by which everything that follows will be judged. Carefully designing anchors can frame a choice or target action.

Availability Heuristic

The information most readily available to us comes to mind first, even if it provides a distorted picture of reality and has a disproportionate influence on our behavior. To paraphrase Daniel Kahneman, all we see seems to be all there is.

Representativeness Heuristic

We all make judgements based on stereotypes. We overestimate the similarity between prototypes we carry in our head and a specific example at hand, ignoring realities such as the likelihood of alternative possibilities or explanations.

Optimism Bias

We tend to downplay the potential of unforeseen problems delaying, damaging or derailing an expected positive outcome. We have a bias for the best case scenario, underweighting evidence of the barriers and delays others experienced in similar situations.

Loss Aversion

We tend to favor preserving what we have over getting what we don’t. Losing $10 feels more significant than winning $10. This can play out as scarcity: When a resource appears in short supply, people think short-term, and even act against their interest to preserve what they have.

Framing Effect

Our interpretation of an event is influenced by how it is presented. Certain attributes or dangers can be emphasized or diminished depending on how the overall event is conveyed, influencing our perceptions of risk and reward, and ultimately altering what we do.

Status Quo Bias

We all have a bias toward the present situation or default, mostly because it’s easier and often feels less risky. All things being equal, we go with the way things are or what appears to be the norm. Change has a higher bar: It must be worth the effort.

Priming

You can influence the choices people make by exposing them to certain stimuli beforehand. Even getting students to focus on a random number has been shown to influence their estimates of unrelated values.

Confirmation Bias

We gravitate toward and emphasize evidence that confirms our current beliefs. We strive to maintain coherence and consistency, and contradictory evidence makes that effort more difficult -- so it can be easier to ignore it or discount its validity.

Empathy Gap

We often make rash decisions to satisfy a visceral emotion, never imagining we may soon be in another state -- what’s sometimes called moving from a “hot” to “cold” state. When you're furious, it can be hard to imagine being calm.

People like to be in control. Feeling control over a decision empowers action by providing confidence that we can make an impact. Choice helps: It gives one the sense of more control.

The perceived cost of an action — in money, time, social capital or even cognitive load — may lead to action or inaction depending on the situation. To achieve a sense of accomplishment, we often tend to finish things we’ve already invested time and energy in; on the other hand, people gravitate to what requires less of them.

Behaviors are influenced by their context. People favor what’s accessible, noticeable, supported or triggered by environmental cues.

As social beings, we can’t help but look to our peers. We are influenced by what we think others do, and by what we think they expect of us – in a word, norms. Norms can be embedded in cultures as traditions or emerge quickly as trends. While often not explicitly acknowledged or even consciously recognized by the people involved, norms are among the most powerful influences marketing can harness.

Norms come in five flavors:

Explicit Norms

When expected attitudes and behaviors are openly expressed or written down, as with laws and rules.

Implicit Norms

When we suspect what’s normal or expected even though it’s not written down.

Descriptive Norms

What we see people like us doing.

Injunctive Norms

What wins approval or disapproval from our group.

Subjective Norms

What we think others expect of us.

The standards we set for ourselves, driven by aspirations, fears and self-image, impact our behavior as we signal who we aspire to be.

Ought Self

What I should be

Ideal Self

What I want to be

Forbidden Self

What I am not allowed to be

Undesired Self

What I want to avoid being

We are always creating our “self” and signaling to others what that self is like. How we do this is driven by our vision of the kind of person we want to be and the kind of person we want to avoid becoming.

Adapted from Bak, W. Self-Standards and Self-Discrepancies. A Structural Model of Self-Knowledge. Curr Psychol 33, 155–173 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-013-9203-4

Our identity and affinity with social groups influences our perceptions and behaviors. We cherry pick data to protect our identity and our perceived value to others. Our need to fit in with affinity groups colors our perceptions of scientific evidence, regardless of our level of literacy with the topic. To motivate change, marketers must initially fit their outreach and asks to the target’s existing world view. Connection always precedes conversion.

1Kahan, Dan M. and Peters, Ellen and Dawson, Erica and Slovic, Paul, Motivated Numeracy and Enlightened Self-Government (September 3, 2013). Behavioural Public Policy, 1, 54-86, Yale Law School, Public Law Working Paper No. 307, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2319992 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2319992