5 Things We Need To Do In This Pandemic — And Why We Aren’t Doing Them

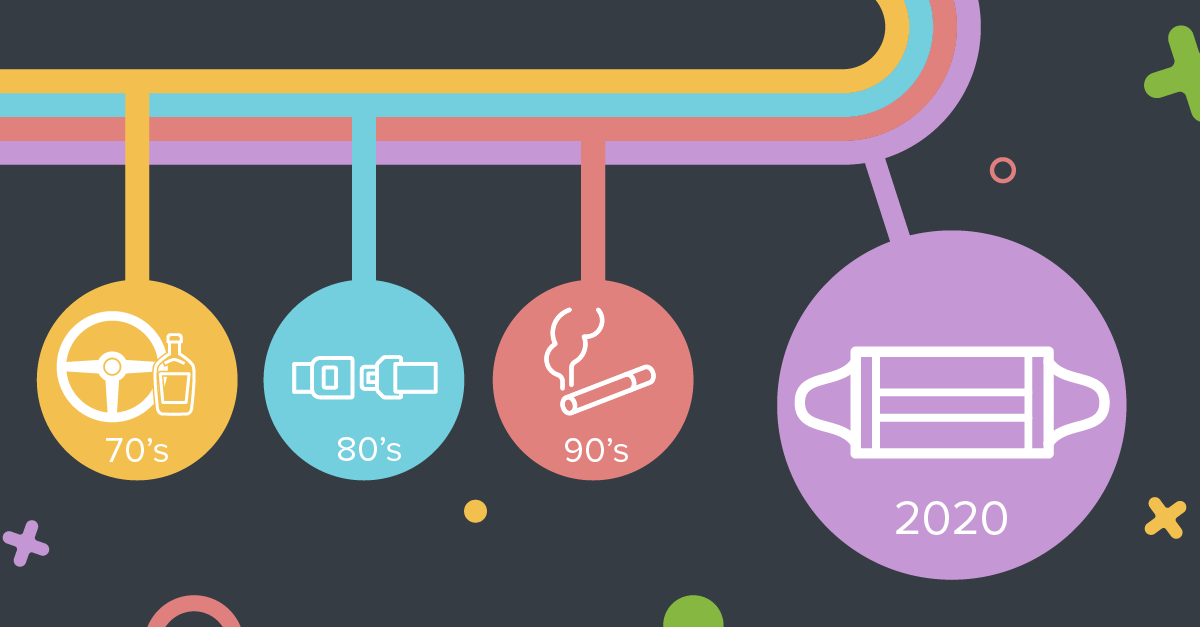

This has happened before: Millions of Americans opting to take mortal risks despite clear evidence they are putting themselves and others in danger. Think drunk driving in the 1970s. Seat belts in the ’80s. Smoking in the ’90s.

People knew what was right. They just didn’t do it … until we, in the public health field, put a marketing mindset to work. Clear rules are important. But they are insufficient to change behavior.

We can’t just create awareness. Motivating people to act requires real marketing. This includes elements like showing and encouraging positive behavior (vs. negative scare tactics that we know don’t work), and building campaigns that speak to what people care about (vs. relying on facts and figures people ignore). It also includes technology, logistics and more.

How do we know this? Because we’ve done it before.

Wearing masks today is like driving sober in the 1970s. We know it’s safer, but we also want to let it slide. Yes, in the 1970s we had laws against drunk driving, but we also expected it to happen, and crashes to continue — much like we expect hurricanes and tornadoes. Mothers Against Drunk Driving toppled those norms and changed our expectations. Eventually, we were not just holding drivers accountable, but bars, judges and politicians as well. We also came up with logistical help — the designated driver.

You can go without a mask and perhaps no one will get sick, just as it’s possible to drive drunk without killing anyone. You are simply raising the risk (and humans are terrible at reacting appropriately to risk). But if you tell someone you drove home drunk today or you do crash your car, you’re unlikely to find a friendly ear or a forgiving judge. It’s not an accepted practice, even as an exception. We’ve moved closer to that on masks as stores like Walmart require masks for entry, sending a signal about what’s socially acceptable — something humans are quite attuned to. But we also need more solutions on the logistics front: How do we meet the human need to gather in-person and mask-free safely, just as we can drink safely if we have a designated driver? Maybe clearer guidelines on ventilation and outdoor use, as well as more accurate and faster testing. Pods also hold promise. Like with drinking, the goal should be reducing risk as much as possible — not trying to enforce a blanket rule that people will inevitably break.

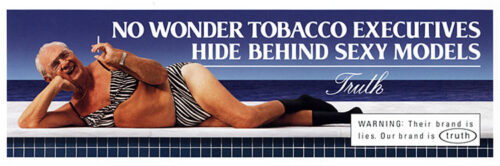

Social distancing saves lives. It’s also a buzzkill, reminiscent of how warnings about smoking felt to young people in the 1990s, when the teen smoking rate was skyrocketing. The turnaround in the youth smoking rate came after public health advocates realized they needed more than a health message. Smoking was, after all, a symbol of rebellion and control — essentially the independence adolescents seek as they come of age. The youth-oriented ‘truth’ campaign, first unveiled in 1998, countered by offering teens what they sought — rebellion, in this case against the tobacco industry. Truth wasn’t adult oppression. It was teenage fun.

The ‘truth’ anti-smoking campaign, first led by Marketing for Change CEO in Florida, sparked the first drop in teen smoking in 19 years.

Social distancing will never be fun except maybe for hermits and monks. But physical distancing — staying 6 feet or more apart — should not mean abandoning the social interactions we all naturally seek. Nowhere is this more true than with young people. Susan Middlestadt of Indiana University and Chris Owens at Northwestern University have been looking at what separates those who follow public health recommendations and those who do not. A major factor, they are finding, is efficacy — can they do it without upending their life? This likely means people’s confidence in their ability to retain their social connections and normalcy in their lives is critical. We seem to be ignoring that. Everything from the very term ‘social distancing’ to our inability to promote social closeness with physical distancing works against this opening. As with youth smoking, a new perspective on how to frame and institute distancing efforts would make the practice more widely adopted.

Immunizations are more important than ever, and we’re not just talking about the much anticipated COVID-19 vaccine. Experts always want us all to get our regular flu shot, but this year it’s critical to prevent a double-whammy of seasonal flu and COVID-19 from overwhelming hospitals. That doesn’t mean people will do it. Again, risk communication and doctors’ recommendations get us part of the way there, but not all the way. Even one of the authors of this nerdy little essay didn’t get a flu shot until his son’s hockey club joined his doctor in asking him to get one. That’s the power of norms again: “I’m a hockey coach and hockey coaches get flu shots, therefore I’m getting a flu shot.” First year in a long time.

Add to this the anti-vax movement — well-meaning if misguided people who do not trust assurances from the CDC and other medical experts that vaccines are safe and necessary. Some people will undoubtedly sit out the regular flu vaccine, as well as any vaccine, if developed, for COVID-19. The job of a public health campaign is to make vaccine coverage more universal, and a big part of that will be framing. We’ve learned from our research on fluoridation that ignoring “anti’s” because their arguments are not anchored in science is a mistake. People who hear them may think they’re crazy, but they also could be on to something. Pardon the pun, but public health experts will need to inoculate Americans against the misinformation sure to emerge with any vaccine.

Ventilation matters in a pandemic the same way as seat belts matter in a car. Seat belts won’t prevent a crash but they reduce your risk of injury and death. Ventilation doesn’t eliminate the novel coronavirus from the air, but it helps keep the virus from finding a new home in your eyes, nose or mouth. For example, Japan has prevented COVID-19 transmission in it’s famously packed subways in part by requiring the windows to stay cracked open. Uber launched its “Wash Wear Air” safety campaign to encourage opening a window during each ride. How can we apply thinking about ventilation to indoor spaces? Should we be thinking about HEPA filters instead of Clorox wipes? Helping people maintain air flow will become even more important as colder weather sets in this fall and winter, and people spend more time in closed spaces. How can we create a trigger that makes compliance more likely (like that buzz if you don’t put your seatbelt on)?

Also remember risk messaging and laws alone only got two-thirds of Americans to wear seat belts. More recent gains came from a twin messaging and law enforcement effort known as “Click It or Ticket.” People can easily dismiss the chance of getting in a crash (won’t happen on this ride), but less so a ticket (now that could happen). Maybe there is a messaging element around a more immediate benefit of fresh air?

Mental health will become a primary public health concern as people face a prolonged period of stress and isolation. From depression and anxiety to working through grief, collectively we are feeling A LOT.

Mental health communications have been quick to promote call lines and self-care strategies to support coping skills now, but we need to be thinking long-term. The big question is: how do we shift from coping to living?

Addressing barriers now is key. Access to mental health services are decidedly different in this post-COVID world, with many providers moving to telehealth or limiting group therapy. Communicating access to the services available, and how they are available, is an information gap we can close as infrastructure reconfigures. There is also the matter of increased demand on infrastructure that is already experiencing limitations.

Unpacking what mental health support includes, and how we can integrate that into our understanding of well-being, is another. Social marketing around mental health issues has long driven the inclusion of mental health into our understanding of health care, of whole person care. Moving forward, we will see the responsibility for supporting mental health spread across different groups. Resources like employee wellness programs will play a larger role in supporting and communicating about mental health to protect a fragile workforce that, in the U.S. at least, already was barreling toward burnout before the pandemic hit.

This is an opportunity to bring a cultural shift around how we talk about wellness, balance and health care more broadly.

To be sure, clear risk communication, rules and enforcement are helpful tools – that’s typically what’s driven the first gains for major social shifts in behavior. But these tools never get you all the way there. In America, if we really want people to change, we have to market the behavior to them.

We’ve learned this again and again in public health. Let’s learn it a little quicker this time.